We find that there is a tendency for leaders in sport to feel they must adopt a heroic approach to leadership. The expectation that an individual needs to be able to take on and solve – often alone – all the problems confronting their team undermines performance and increases stress within clubs. This narrow view of what makes leadership effective is reinforced by the journey many leaders go on – working their way up in a particular discipline, often with limited external exposure, even to other sports.

There is no such thing as a “correct” leadership style.

Instead, in our work with senior executives across different clubs, we de-emphasise the idea of a “correct” leadership style and instead emphasise the importance of self-awareness and the ability to playback recent experiences to develop a leadership playbook. We know from experience that the most successful leaders vary their approach depending on the scenario. When we ask people who flex theirs how they think about leadership, the most credible answers are always those founded on a high level of personal self-awareness.

You don’t have to be super reflective to be self-aware; it’s a skill that can be learned.

While some people are more naturally reflective than others, becoming self-aware in leadership comes from practice and a desire to challenge oneself and seek feedback. This ability to reflect is incredibly important in enabling individual leaders to step into different roles, whether moving up or sideways in an organisation. Marshall Goldsmith makes this point in his book, What Got You Here, Won’t Get You There, as the skills to succeed in your previous role often need to be revised and sometimes unlearned to be successful in your new one.

Successful leaders recognise which skills need to be amplified and which need to be dampened.

One of the most common challenges when working with leadership teams is getting good-quality feedback on what’s going well and what needs improvement. Part of the problem is that, despite sport being a feedback-rich environment, it could be better at providing feedback when results are less evident. Understanding yourself in the context of leadership requires a degree of discomfort and a desire to put yourself out there, to attempt to learn about the reputation you have when you aren’t in the room.

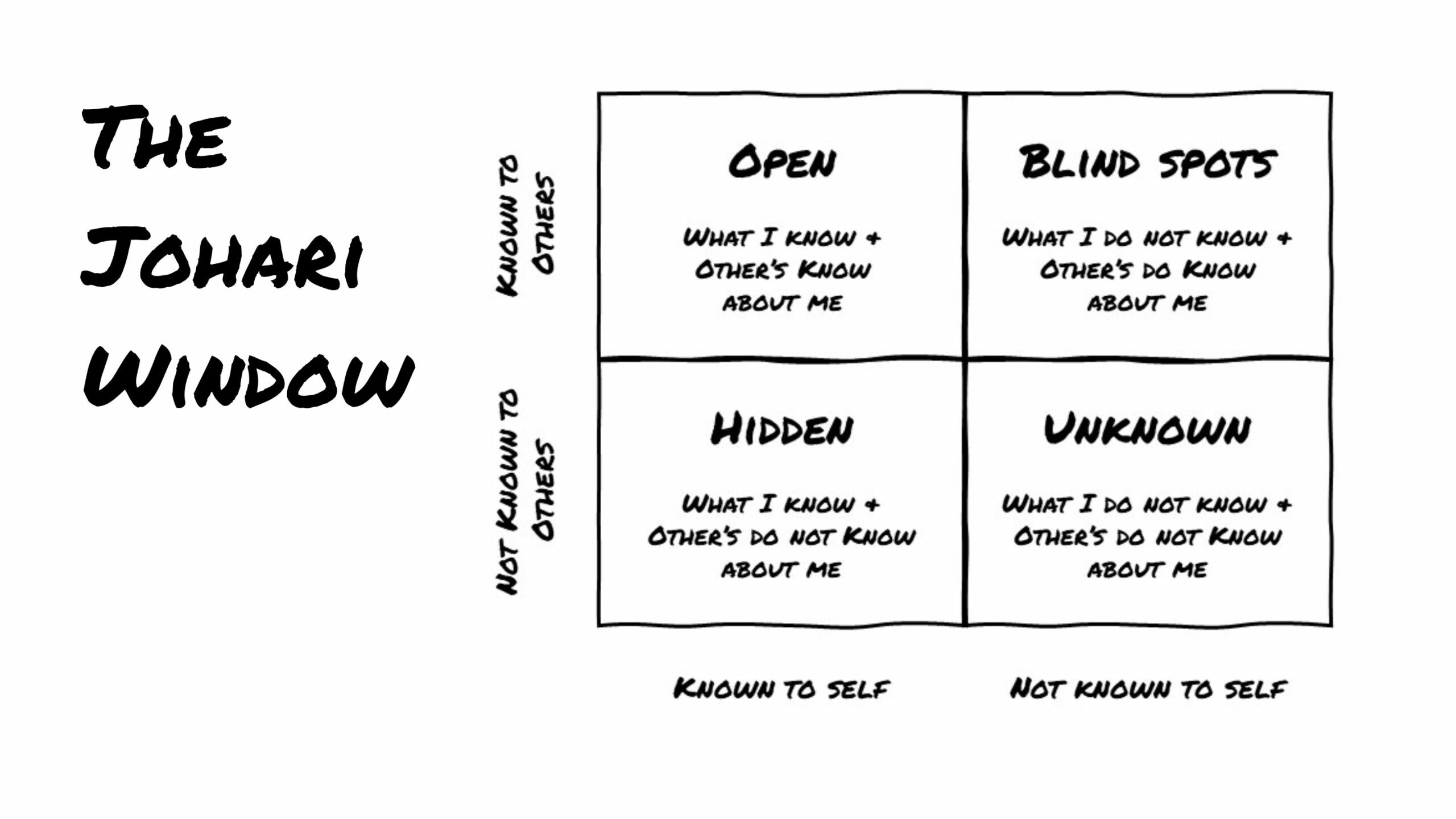

The Johari window is one tool that might help you identify potential blind spots.

We frequently come back to the Johari window (if you want to know more, Mindtools provides a useful summary). It invites people to consider four essential areas of knowledge. Each quadrant has positive and negative leadership attributes; what matters is that you grasp what they are and how you play some up while downplaying others. The four quadrants are as follows:

- Open – I and others are aware. These are the things that most of us have on our CVs and are proud of, yet they may also be tendencies that we are aware of (for example, talking over someone when we are animated).

- Hidden – I am aware, but others are not. They are more personal; they may be ideals and beliefs that shape your outward behaviour but are not expressed. We frequently find that positive attributes hidden from others are worth displaying, especially when they are crucial to your motivation.

- Blind area – I’m not sure, but others are. This is the problem box. These are characteristics you are recognised for but do not recognise yourself. We frequently encourage people to consider any comments that have surprised them. Knowing what attributes are in this box is a critical aspect of leadership development – and often the most difficult – since it gives individuals the most chance to influence and modify their reputation.

- Unknown – I don’t know, nor do others. The stretch box. While self-awareness begins with comprehending what you and others know about yourself, the true leadership challenge is determining what is in the unknown box – the abilities and attributes you may have to acquire to keep moving forward.

Look to the future.

The challenge for senior leaders is paying attention to the unknown box as they develop their leadership skills. Looking back tells us who we have been, and while this is essential information, it rarely teaches us how to react in a new role. As your leadership objectives and role change, you must look ahead to who you want to become. London Business School Professor and author Hermina Ibarra has shared some fantastic insights in this area. To take on a new leadership position, you must act your way into it by experimenting with new ways of doing your work, forming new relationships, and continuing to work on yourself. Only through experimenting can you explore the unknown box and affect how others perceive you. In a recent conversation with Lucy Pearson, Head of Education at the Football Association, she described this as ‘finding’ – as opposed to ‘minding’ – the gaps.

Leadership development requires feedback, and you need to create efficient feedback loops to give you the ability to iterate and adapt as you act your way into leadership. We draw on Marshall Goldsmith’s work to inform the four steps we recommend emerging leaders implement to create an effective feedback loop.

- Inform people about what you are attempting to change. Discuss what traits you are boosting and dampening. Inform individuals about your project and that you require their assistance (in a kind way). You’ll be amazed at how big a difference this makes.

- Request feedback and then express gratitude. One of the most common errors we all make, especially when soliciting feedback on ourselves, is asking for input and then defending – explaining why we did something or giving our viewpoint. Once you’ve done that, it’s a long journey back to honest feedback.

- Listen to yourself and others. We constantly receive feedback, and we do not hear it. Make a promise to write down all the feedback you receive throughout the day. Consider what it says about the strengths you discuss. Most of the time, the things we think are our strengths – the things we brag about – are our flaws. Pay close attention.

- Check what your relatives and friends think. When you receive feedback, ask yourself, your friends, and your family whether it is true. Would your spouse agree with the suggestions? If they would, it’s probably accurate.

Leadership is a journey and one you actively need to navigate.

Related Posts

Building high-performance environments off the pitch in elite sport

September 28, 2023

0 Comments8 Minutes